Yasuní National Park in Ecuador has been called a biological bulls-eye. Biologists have counted to over 600 species – in a hectare of forest. (As a comparison there are around 40 tree species in the whole of Sweden). Due to the location at the intersection of the Equator, the Amazon and the Andes, this is probably the most species-rich place on Earth.

It was my childhood dream to come to the rainforest, to a place where life has so many expressions. But when I encountered Yasuní, during fieldwork for my master’s thesis on rainforest restoration, the dominant emotion was dismay. There were large signs with the names of oil companies on them. How was it possible – here, in roadless land in the Amazon? A mental abyss opened up. If this place – with its unique biodiversity (I mean, pink river dolphins!), uncontacted indigenous peoples, all the protection a land area can have – cannot be exempted from exploitation, then what can be protected? Nothing? The Amazon rainforest is one of the tipping points that could destabilise the entire climate system of the planet if pushed hard enough. Scientists describe how that point is now approaching. Drilling for oil here can only be called madness.

As Canada’s forests burned from east to west (more than 120 000 square kilometres have burned this year, a doubling of the previous record), the legendary Burning Man festival in the Nevada desert was drenched in rain and mud. ”it seemed someone had changed the Burning Man tape from its signature Mad Max-esque scenes to Waterworld” as one seasoned burner put it. Media reported on how people were stuck in what would have been a party in the usually sun-drenched Black Rock City, the temporary metropolis that gathers 70,000 people every year. As the roads were impassable after the rain, organisers launched a ’Wet survival guide’ urging visitors to conserve food and water and look after each other. The festival’s finale, the burning of the wooden effigy The Man, had to be postponed. For once, it was celebrities and Silicon Valley’s tech elite who were affected by extreme weather. Unlike most of the victims of climate change, they were able to go home after a few muddy days.

Allen Ginsberg’s poem Howl,* which begins ’I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness’, also features a burning man, Moloch. What sphinx of cement and aluminium bashed open their skulls and ate up their brains and imagination? asks Ginsberg, and answers:

Moloch! Solitude! Filth! Ugliness! Ashcans and unobtainable dollars! Children screaming under the stairways! Boys sobbing in armies! Old men weeping in the parks!

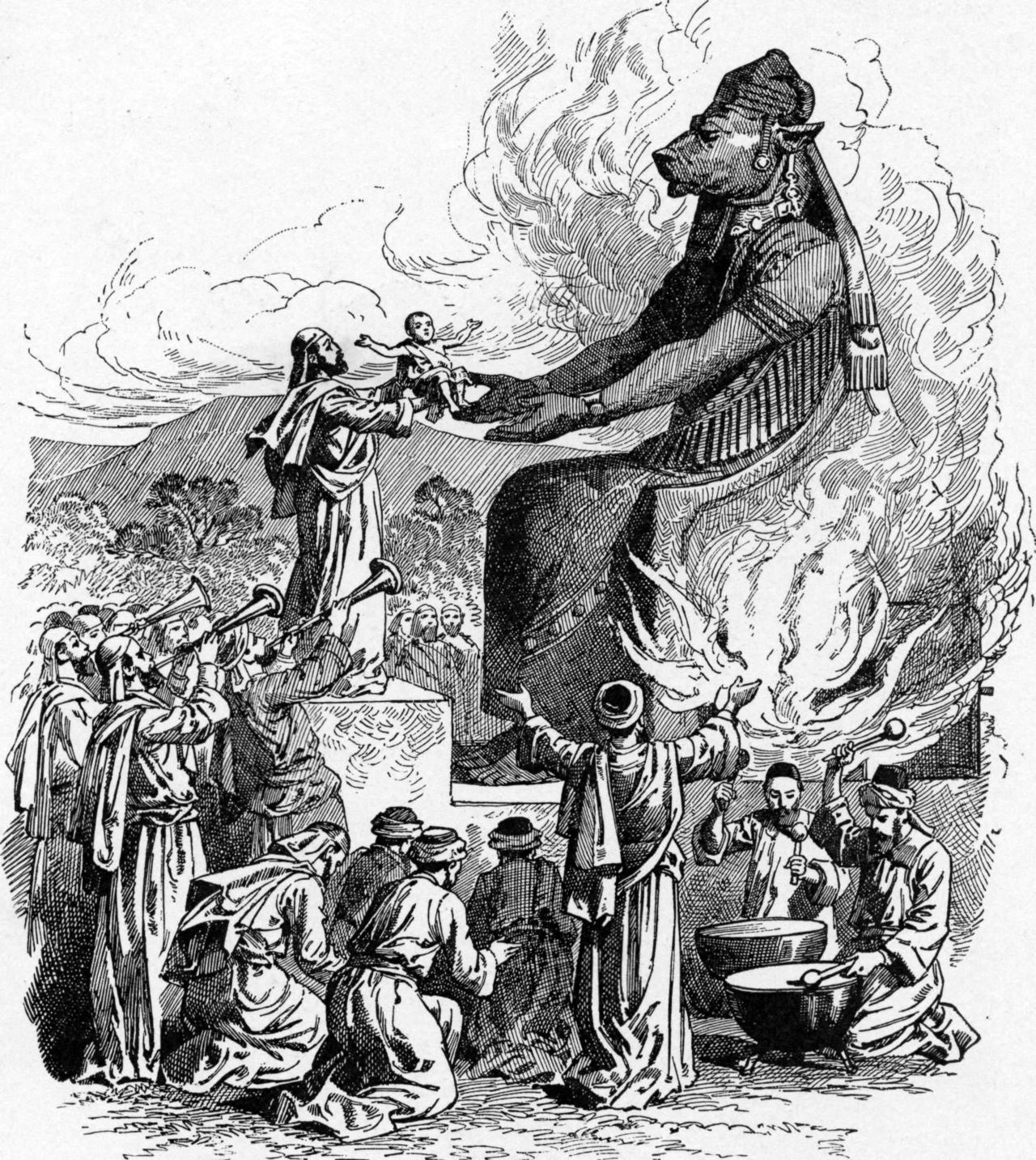

Moloch is mentioned in the Bible as a god or demon who demands child sacrifice. A terrible beast. No wonder Moloch appears so often in culture, from Tennyson to Sergio Leone. He is depicted as a bull-headed figure, with a fire burning inside where the unfortunate little ones are thrown in to be consumed. In Ginsberg’s poem, Moloch is rather a personification of the industrial growth culture: Moloch whose mind is pure machinery! Moloch whose blood is running money! Moloch whose fingers are ten armies!

Offering to Molech. Illustration from the 1897 Bible Pictures and What They Teach Us by Charles Foster.

We are all, to some extent, stuck at a fossil-fuelled party. As the forests burn, we sacrifice our attention to screens where Moloch gets another click, another view. All the information about the state of affairs is in front of our eyes, but Moloch is eating our brains and our imagination – we are apparently collectively unable to react and stop the sacrifices. Even writing this feels lame. What is really new? The madness is mundane, nothing to raise eyebrows about. Moloch’s offer is the same as always: throw what you hold dear into the fire, and I will give you power.

Recently, he has been talked about (by Liv Boree and Daniel Schmachtenberger) in the context of the exponential development of artificial intelligence. I see the best minds of my generation developing the mind of Moloch. Whatever one thinks of the likelihood of AI killing humanity, it certainly brings new levels of efficiency to the system that is rapidly consuming the living world. In Meditations on Moloch, Scott Alexander describes his mystical experience, standing in a Las Vegas skyscraper one evening, looking down on the illuminated city and marvelling at how such a thing could be built. ”Like, by what standard is building gigantic forty-story-high indoor replicas of Venice, Paris, Rome, Egypt, and Camelot side-by-side, filled with albino tigers, in the middle of the most inhospitable desert in North America, a remotely sane use of our civilization’s limited resources?” Las Vegas is also a temporary metropolis. Perhaps there is no philosophy in the world that supports its existence, Alexander muses. Las Vegas may be extreme, but Moloch is working around us all the time. Since Ginsberg’s poem, world energy consumption has quadrupled. Cement production has increased by over 30 times. Since 2020, the mass of human made things exceeds the amount of biomass. There are now more buildings, roads, mobile phones and Barbie dolls than there are forests, krill and bears. The amount of plastic alone exceeds the amount of animals.

The theme of the rain-soaked Burning Man was ANIMALIA, a celebration of the animal kingdom and our place in it. In-house philosopher Stuart Mangrum writes that ”Of all the strange ideas that humans hold about the animal world, perhaps the strangest is the notion that humans are not in fact part of the animal world; that we have somehow evolved beyond our animality and now occupy a position apart from and superior to the rest. The myth of human exceptionalism has deep roots, fueled by thousands of years of religious cant, philosophical excuse-making, and scientific hoo-ha.” This idea of separation, which has spawned the perception of world as object, measurable and manageable like a machine, is the DNA of the industrial-growth-society-Moloch. Using the technology developed from this understanding – AI most recently – it builds itself a body. Moloch requires constantly increasing amounts of energy, whether that means mining on the moon or at the bottom of the ocean. Even if it means sacrificing the richest forests on the planet. Even if we perceive the madness, we don’t know how to stop feeding it.

As long as our idea of development lies within this idea-DNA of increasing dominance and control over nature for human use, we will continue to sacrifice to the Moloch machine. Our collective actions shape the madness. But there are seeds of other ways of being human. While the tech billionaires packed their solarpunk gear into 4×4 vehicles and headed for the Nevada desert, a referendum was held in Ecuador. The question: whether to continue to allow oil extraction from Yasuní, or let the oil stay in the ground indefinitely and forgo billions of dollars in export revenue? The result: a resounding yes to nature. With over 5.5 million votes in favour of quitting the oil extraction and 3.8 million votes against, this is perhaps the most powerful opposition to the fossil fuel industry the world has ever seen. How was this possible? We can’t just let go of ideas, we have to replace them with others. An interesting factor in this context is that Ecuador is the first, and so far the only, country where nature has rights enshrined in the constitution. In other words, there is an institutional basis for the understanding that not only humans, but everything that lives, has intrinsic rights to exist. This involves a renegotiation of the role of humans and changes what seems reasonable to do or not to do. Understanding other living beings as subjects rather than objects is a challenge to human exceptionalism. This constitutes institutional support for a more healthy, indeed more true, perception of our place in the living whole. Only with this shift in worldview will it be possible to stop feeding the fire of Molok and shift from a culture that eats life to a culture that honours life.

*Howl is described as a catalyst for an earlier counter-cultural movement, the post-war beat generation.